I like to read a local book when staying away from home. It's a habit I began about twenty years ago when I happened to read Captain Corelli's Mandolin on a Mediterranean island and, even though it was the wrong island, the book came alive.

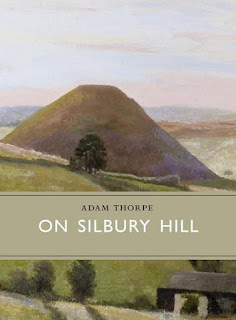

We've been staying a few miles down the road from home, in Castle Combe; proof positive that you don't have to get away far to get away. In a bookshop in nearby Corsham I asked the friendly proprietor what to read. I wanted something that wasn't a guide book but was good writing, evocative of the area. She gave me a fine selection but On Silbury Hill by Adam Thorpe stood out. It has been an amazing companion; a metaphysical, biographical introduction to the area known as the Wiltshire Downlands covering six millennia of history from Neolithic times.

We went to Avebury and Silbury Hill. As Adam Thorpe (almost the same age as me) recalls his Marlborough College school-days so I recalled my own, not least because in about 1967 I came there on a school trip.

To be fair I can remember only one incident clearly from the trip. Walking from what was probably then the coach park to the hill we were approaching a gate and Max Oates ran at it and cleared it in, what I later found out was actually called, a gate-vault. Max arrived at King Edwards (a place that gave an experience not unlike Marlborough but was not a boarding school and thus reduced the bullying hours somewhat) as a highly proficient gymnast and diver. My reaction, as one who had been convinced that getting into King Edwards was a verdict on my all-round genius, was 'Why can't I do that?' It was one of the first of many steps to realising that in order to really get on you have to be more than a smart kid. I grew up in a big old house but it was rundown and we had little money for much of my school-days. I got a free place through the entry examination. But I hadn't had gym classes, diving lessons or the pushy parents to lead me to young specialism. Indeed I spent my secondary school days trying out every new opportunity and moving on. Fives, squash, hockey, rugby, cricket, tennis - I never settled, always looking wistfully over my shoulder at the sacrifice of going to a school that thought rugby football was the only type of football worth playing. I also had undiagnosed asthma, which meant my shortness of breath when running was treatable (and eventually was, aged 24) but I merely thought I wasn't very good at it and kept trying harder.

Silbury Hill is an enigma. The conclusion of most experts, after two to three hundred years of modern archaeology, is that they don't know what it is. It is a thirty metre high mound in the middle of a huge natural downland amphitheatre. It is the largest human-made mound in the world and is near the largest standing stone circle in the world. The secret it has revealed is that it was human-made over a couple of hundred years and has at least twelve cycles of layering. It reminds me of a a cairn where every newcomer places a stone. Except that generations have placed huge layers of chalk, turf and sandstone without, or at least without us being able to tell, if of any of them had the first idea of what the point was.

So today it just sits there, next to a busy road. Visitors are not allowed to climb because of erosion although we saw two do so during our brief visit. They would have had to squeeze through a gap, ignore two notices and climb a fence so I guess they knew what they were doing. Walking a mile away to West Kennet Long Barrow the Silbury Hill becomes small - looks like a spoil heap in the wrong place.

The Standing Stones, Barrow and Hill are accessible without paying. It has managed to resist becoming the downlands visitor experience although there is some of that in the museum and nearby Avebury Manor and Gardens (National Trust). Otherwise local agriculture simply lives and works alongside.

On a grey February day the place conjured up all sorts of alternative thoughts. It's not what some theologians call a 'thin place'. I felt it was a full place. When we don't know what something means everyone has a go at defining it. It's become somewhere with too much meaning - none of it that helpful. It's a reminder of people keeping their eyes on something bigger, grander and out there. A striving for meaning. A desire that the point of all this be something other than my own self-actualisation. Which is, at the very minimum, what the Christian Gospel does; it anchors the truth elsewhere.

Avebury and Silbury change your vision by looking at the work of people who bothered to change their horizon. The lack of clarity about why they did it leaves their work as the record of a universal question.

The book is a knowledegable friend on the same journey.

No comments:

Post a Comment